Death by a thousand cuts

Anyone who has run a large operation will be familiar with the constant demand to do more work with less people to save cost. When I say demand, that’s putting it a bit passively. It’s more often imposed than demanded. Hiring freezes are implemented or a proportion of the headcount is simply removed from the budget. 10% always seems to be a popular number.

The first few years this happens things are ok. People find a way of managing. Any slack in the system is removed. “Non-essential” work stops being done: training, then team briefings, then one to one development meetings with line managers until there is nothing left to cut.

Then it starts to bite. Back-logs of work begin to build, service deteriorates and quality suffers. Things start to go wrong.

If you find yourself in this situation, how do you stop the vicious circle and find a way to do more with less?

The Capacity See-Saw

Capacity in any operation can be thought of like a see-saw. On one side is the demand from customers: the work to be done. On the other is the supply of people to do that work.

The see-saw needs to be kept in balance for the operation to do what it’s designed to do effectively and efficiently.

But blunt attempts to save cost can cause an operation’s see-saw to tip out of balance. The supply side gets chipped away at until there are no longer enough people to do the work required.

What can you do to re-balance the see-saw? Let’s consider each side in turn.

The Supply Side

There are a number of things you can do to increase the supply side. Assuming you can’t hire more people, overtime might be an option. Better scheduling of people to match the peaks and troughs in customer demand may help. Reducing non-productive time might help too. Managers don’t tend to struggle with thinking about the supply side. Their natural inclination is to throw more resource at the problem. But assuming you’ve done all this and are still stuck with an operation struggling to deliver service, what then?

The Demand Side

I often find that operational managers consider the demand side of the see-saw, the work-load, to be a given and therefore largely un-improvable. After all it’s the work demanded by customers and customers need to be served. But analysing and improving the demand side of the see-saw is often the most effective lever you have to improve service performance. Let’s take a look at an example.

A Back-Office Example

I worked with a client once who found themselves in the position described at the beginning of this post. They had a back-office operation staffed with over 100 people. Each person worked complex cases which took a large number of tasks over several months to complete. Each of these people would have a couple of hundred of these cases to work simultaneously. A case management system was used to manage all the work. These are systems which prompt case handlers to perform tasks. If you are not familiar with them, imagine email on steroids. Do this, check that, remember this. If you’re one of the members of staff trying to do this job, I would imagine it’s like having both feet tied together and then being asked to run a 100-metre race.

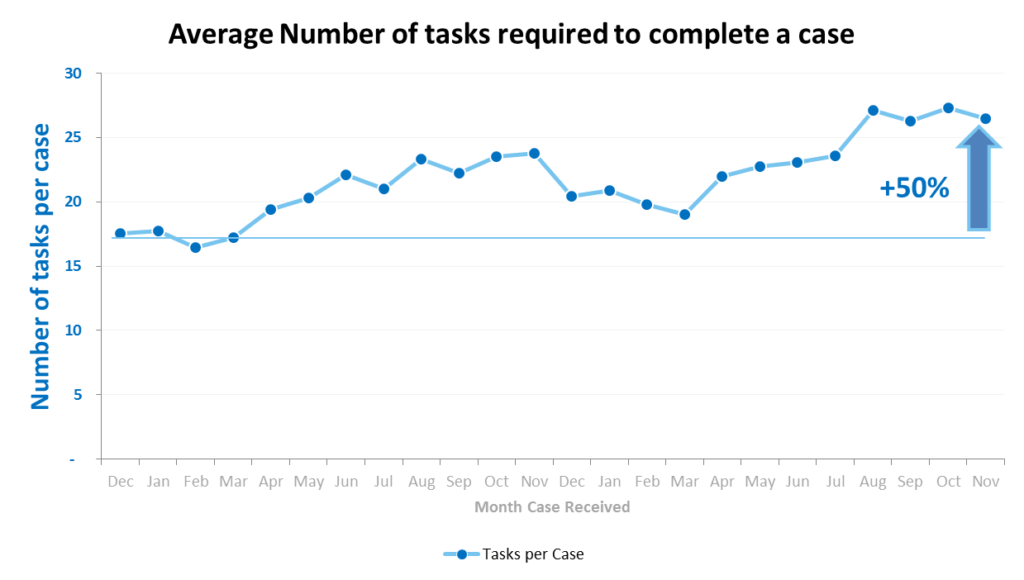

We started by measuring how many tasks it took for a member of staff to complete a case:

This showed that the work required to complete a case had increased significantly over time. It was up by 50% in the last 2 years alone!

Organisational Scar-Tissue

In this operation, as headcount had been cut, the case load of each handler increased. Service deteriorated as people struggled to keep on top of all the work and errors increased. These errors were costly to rectify, so the management team implemented more tasks and checks into the workload to make sure things didn’t go wrong again. These checks were never reviewed to see if they were still relevant and accumulated over time like organisational scar tissue.

You would need more people in this operation just to stand still, but they had fewer staff due to the cuts in headcount.

Imagine how it would feel to be one of the workers in this operation. You’re trying your best to do the job asked of you. Your focus narrows as you try to clear all those tasks whilst at the same time making sure you don’t get penalised for failing your quality audit. The purpose of the job has changed from how do I best serve this customer? to how do I keep on top of my tasks and pass my quality audit? A subtle shift, but a fundamental one from the customer’s perspective.

How do we stop this vicious cycle?

Taking the Customer’s Perspective

We took the list of all the different tasks the employees in this operation were asked to complete. We analysed each task and asked a simple question: does this task move the case on? If you were the customer and saw what was being done, did that activity move the case towards completion or not?

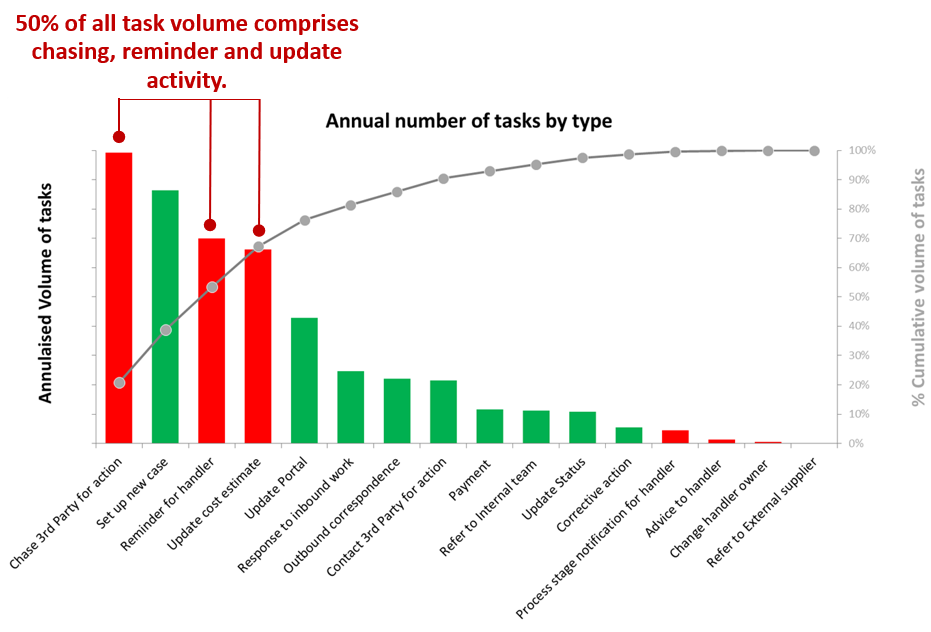

The chart below shows the make-up of all tasks by type. Each type is coloured either green or red. Green tasks move the case on towards completion and involve either processing some work or asking someone to do something. Red tasks don’t move the case on. They are invariably reminders, chase activity or asking for status updates.

Here’s how it looked:

There are two main things to notice from this chart:

1) By ordering the bars by largest to smallest task volume, we are making use of the pareto or 80/20 principle. This tells us that roughly 80% of the outputs of any process are caused by roughly 20% of the causes. In this case 75% of the workload is caused by the top 5 categories. By using the 80/20 principle we’re focussing in on the few things which matter.

2) 3 of those top 5 task categories are red and so do not move the case on. They are checking or re-evaluating but not actually doing anything to move the work on for the customer. Those 3 categories made up 50% of all tasks being completed!

The key to fixing this and reducing the amount of waste activity involved balancing the work-load with the risk. It had been too easy to add checks and controls into the process without understanding the implications for capacity.

Some of these tasks were decommissioned, some were reduced in frequency. Some were replaced with ordered exception lists so that handlers could see which cases most needed urgent attention without having to manually work through and clear every task on a case.

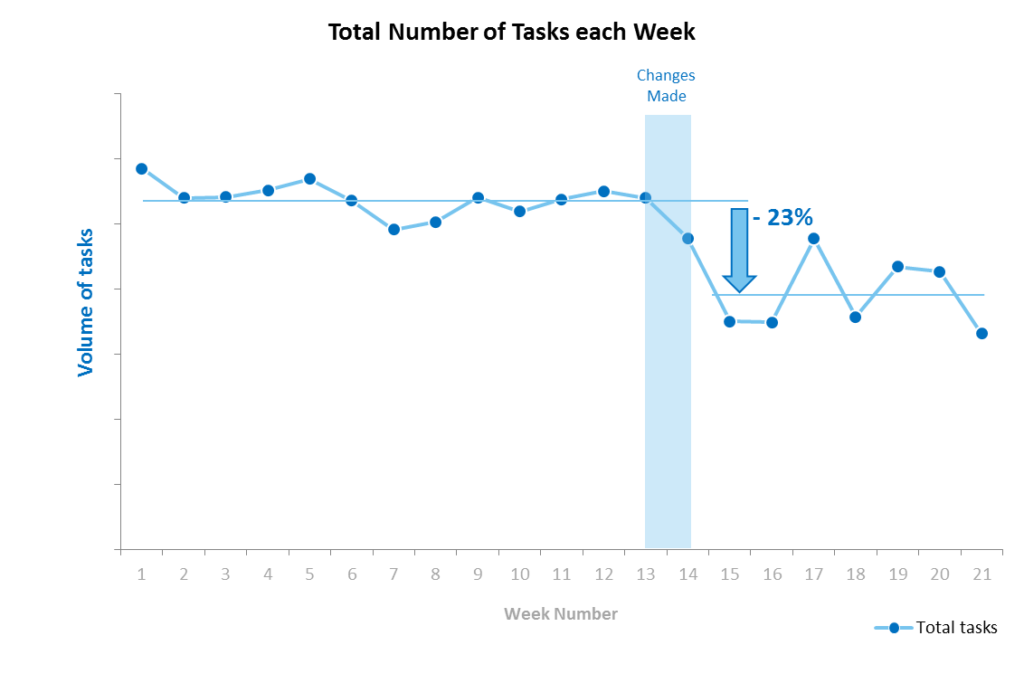

Here’s what happened:

The total volume of tasks each week reduced by nearly a quarter. Now not all those different tasks took the same amount of time to complete, so this reduced the total workload by 15%. This was worth several hundred thousand pounds a year in staff costs and service and quality both improved as capacity was brought back into balance.

In Summary

When you are faced with the call to do more with less and service and quality are already suffering, think about the operational see-saw. What is the work your people are doing for you comprised of and how is it designed? Analysing and improving their work-load is often the most effective lever you have for improving service performance.

Process

Process